Posted On: Wednesday - September 4th 2019 5:54PM MST

In Topics: History Science

Anyone? Anyone? Gore?

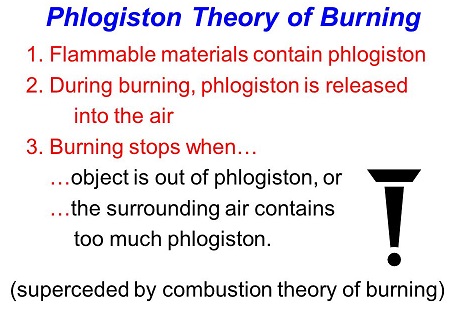

Way back, in our post Towards Sustainable Stupidity*, we compared Stupidity to the theorized substance called "phlogiston". Phlogiston was a substance theorized to be a part of the combustion reaction, in order to explain the results of scientific experiments conducted in this area.

Per this American Chemical Society page on this chemistory (chemical history?),

Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier forever changed the practice and concepts of chemistry by forging a new series of laboratory analyses that would bring order to the chaotic centuries of Greek philosophy and medieval alchemy. Lavoisier’s work in framing the principles of modern chemistry led future generations to regard him as a founder of the science.Mr. Lavoisier left behind the old Greek elements of Earth, Air, Fire, and Water, as understood by Aristotle, to try to explain what was being researched his age of modern chemistry, in which actual experiments were being done. Much earlier in the 1700's, German scientist Georg Ernst Stahl had proposed this invisible (and weirder yet, capable of flow through solids) substance to explain this: When many substances, such as a normal fuel, were burned in air, at the end of combustion, the product, ash, weighed less than the initial fuel. The explanation was the phlogiston was released via the reaction.

It got more complicated, though, when reactions of metallic substances resulted in a GAIN in mass as they were heated. That had to be explained. These guys already had the conservation of mass concept ingrained in them, so the reaction had to involve a product that had a negative mass.

Sure, that sounds crazy, but it's really rather creative. It's not like the real details of the 4 forces of physics (or is it more now, due to more government funding? I haven't been keeping up with the lit-ra-toor) were all known about. What was mass on the chemical level, before the basic particles of atoms were known? Newton had developed his theory of gravity, but who said "m" had to always be a positive number? This negative mass of the phlogiston was part of a theory that still was the best explanation scientist had, at least the ones that weren't DENIERS.

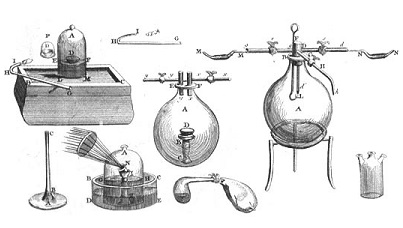

Keep in mind, there were no spectrometers and precision flow meters and the like. This was the kind of equipment the scientist of the time, and up through less than a century ago had to work with. It was all glass, flasks, beakers, tubes, with some rubber and leather products for seals of different sorts and mechanical scales and balances.

Down further in this same article, we see that the science was not settled.

In experiments with phosphorus and sulfur, both of which burned readily, Lavoisier showed that they gained weight by combining with air. With lead calx, he was able to capture a large amount of air that was liberated when the calx was heated. To a suspicious Lavoisier, these results were not explained by phlogiston.Now that's some brilliant science and the reason that Mr. Lavoisier is considered the father of modern chemistry.

Although Lavoisier now realized that combustion actually involved air, the exact composition of air at that time was not clearly understood. In August 1774, the eminent English natural philosopher Joseph Priestley met with Lavoisier in Paris. He described how he had recently heated mercury calx (a red powder) and collected a gas in which a candle burned vigorously. Priestley believed his "pure air" enhanced respiration and caused candles to burn longer because it was free of phlogiston. For this reason, he called the gas that he obtained from decomposing mercury calx “dephlogisticated air.”

In Paris, the intrigued Lavoisier repeated Priestley's experiment with mercury and other metal calces. He eventually concluded that common air was not a simple substance. Instead, he argued, there were two components: one that combined with the metal and supported respiration and the other an asphyxiant that did not support either combustion or respiration. By 1777, Lavoisier was ready to propose a new theory of combustion that excluded phlogiston. Combustion, he said, was the reaction of a metal or an organic substance with that part of common air he termed "eminently respirable." Two years later, he announced to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris that he found that most acids contained this breathable air. Lavoisier called it oxygène, from the two Greek words for acid generator.

At this point in the post, I want to make sure the reader does not think I'm being facetious about all this. See, the title of this post may not mean what one would think it means at first glance. My point is absolutely not that this 350 y/o wayward theory of the composition of substances was an instance of "historic stupidity". On the contrary, I think that those who have disdain for the great work of the "giants" whose shoulders modern scientists stand on, are the ones showing historic stupidity.

It's easy to be smug about the degree of intelligence of the people back in history, as we live in comfort and prosperity. I can remember in high school history classes thinking that people of 100 years back, not to mention 1000, were just all much, much dumber that our crowd (it was not even a particularly stellar high school!) As for science, I'd felt the same way. These people were screwing around with flasks of this and that, dropping stuff off of leaning towers** and stuff, while we had rocket engines putting out 750 TONS of thrust.

Nope, the humans in history, at least of the Western world, were no dummies, just people living their lives at the level humanity had achieved. Their scientists were just standing on the shoulders of a much fewer number of giants. I will write another post on the science/engineering aspect another time.

PS: I found the ACS article the best source on this history from just a cursory search, though the Wiki article is fine. This science blog, written by a lady PhD is a little flippant and in my opinion, has a little of that disdain for those scientists of the past. Finally, this last one is a very quick summary of the history, and has a silly video at the bottom that gave me the first clue (in > 3 decades since chemistry class) that phlogiston is pronounced flah'-gis-tin (accented on the 1st syllable), not Flow-gis'-tonn (accented on the 2nd). Who knew? There's no way I'll ever get this pronunciation correct at this late date, and should I really care?

Maybe I should care, come to think of it, were I the type to be concerned and all about this Global Climate DisruptionTM thing. I mean, that phlogiston theory has the advantage of carbon neutrability, and who doesn't want a world that is carbon neutral?

* One of my best titles, if I do say so myself. Also, my promise to write on this topic was at the bottom of the post Nat-Geo and the once great Royal Scientific Societies - Part 2, in which I gave appreciation to the wonderful science and scientific societies of the past.

** No, I don't think that's the real story, as Galileo Galilei's idea of a constant gravitational acceleration was most likely not really tried, and air drag would have caused it to be an invalid test anyway. Still, Mr. Galileo's curiosity has remained with the Western world, in projects such as David Letterman's dropping of objects off buildings, and then, of course, those fabulous gentlemen of modern science, the Mythbusters. (Yes, that last part was indeed facetious!)

Comments: